“One Ring to rule them all”

— J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings

LibreOffice is now build by one instance of make that is aware of the whole dependency tree. According to my master development build (that is: a build without localization, help, extensions) yesterday, this instance of make now knows about

126.501 targets from 1.717 makefiles

and has a complete view of how they relate to each other. The memory usage of make is at 207 MiB, only slightly overshooting the initial estimations done in the early days of gbuild of 170-190MiB (counting in that the codebase changed a lot in two years, the estimate is actually really good). Given that recursive make is considered harmful and that LibreOffice — one of the biggest open source projects, with huge dependencies and doing releases on three platforms (Windows, OS X and Unix — a lot more if you separate the different Unix flavours), can do this — there is little excuse left for other projects to not follow suit.

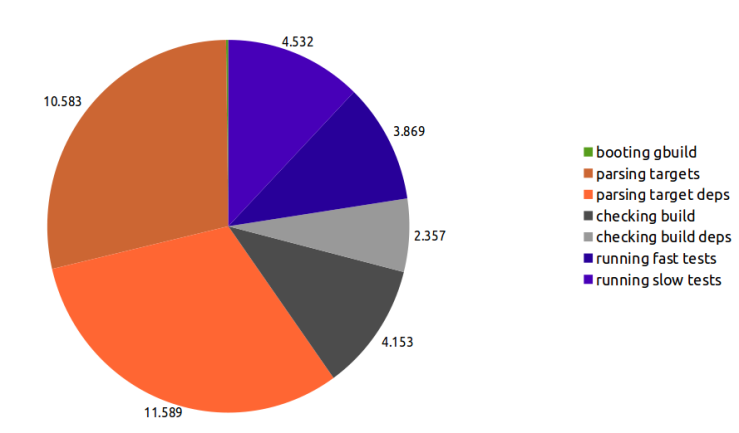

On my machine, checking if anything needs to be rebuild in LibreOffice now takes ~28.7sec (or 37.2sec when also running the default sanity checks along that). That might sound a lot, but consider the scale! And it is a long way from the old OpenOffice.org build system that we came from: Just from my memory, it took about 5 Minutes to do that on the old build system. On Windows it took almost 30 Minutes to find out that there is nothing to do. One of my earliest talks (Slide 29) on the topic of gbuild compared the performance of partial build, if you find these numbers hard to believe. Oh, and of course you still can check for updating only a subset of LibreOffice (a “module” – e.g. Writer) and that takes only 2-3 seconds even for the biggest ones.

Does this difference in performance matter? As Linus argued to eloquently in his google tech talk on git: Yes, it does. Because it enables different ways to work, that just were not possible before. One such example is that we can have incremental build tinderboxes like the Linux-Fedora-x86_64_22-Incremental one, which comes with a turnaround of some 3-5 minutes most of the time by now and quickly reports if something was broken.

There are other things improved with the new build system too. For example, in the old build system, if you wanted to add a library, you had to touch a lot of places (at minimum: makefile.mk for building it, prj/d.lst for copying it, solenv/inc/libs.mk for others to be able to link to it, scp2 to add it to the installation and likely some other things I have forgotten), while now you have to only modify two places: one to describe what to build and one to describe where it ends up in the install. So while the old build system was like a game of jenga, we can now move more confidently and quickly.

Then there is scalability: The old build system did not scale well beyond 4-8 jobs as it had no global notion of how make jobs where running. As we see CPU architectures become more important that have slower, but cheaper cores, this is getting increasingly relevant. Do you have a 1000 core distcc cluster you want to testdrive? LibreOffice might be the project you want to try.

Finally, the migration to gbuild is a proof of how amazing the community is that is growing around the project: While I set up the initial infrastructure for gbuild, the hard work of migrating over 200 modules (each the size of your average open source project) to it without breaking on one of three platforms or disrupting the ongoing development on features and bugfixes was mostly done by a crowd of volunteers. Looking back, I doubt the migration to gbuild would have been completed in reasonable time in an environment less inviting to volunteers and contributors — it was the distribution of the work that made this possible. So the credit for that we now can profit from the benefits of gbuild really goes to these guys. Big kudos for everyone working on this, you created something amazing!

Addendum: This post has been featured on lwn and led to a spirited discussion there.

Notes:

For estimating the number of targets, I used:

make -f Makefile -np all slowcheck|grep 'File.*update'|wc -l

For the memory usage:

pmap -d $(ps -a|grep make|cut -f1 -d\ )|egrep -o writeable/private:.[0-9]+K|cut -f 2 -d\

You must be logged in to post a comment.